The dominant economic paradigm (globalized capitalism) is predicated upon the maximization of profit and unbridled growth (of production and consumption of goods and services).Our economic system determines value and worth based upon quantities (usually monetary) rather than qualities (such as health of ecosystems and quality of life). Because economics is a highly abstract and decontextualized discipline it is unable to anticipate unpredictable systemic events such as economic breakdowns, or acknowledge the ecological limits of the planet and fundamental human needs. The Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman argues that economic theory has become “spectacularly useless at best, and positively harmful at worst.”

Instead of raising living standards and improving human well being and happiness, economic growth has become a root cause of many wicked problems. These innumerable forms of environmental degradation, inequitable wealth distribution, the loss of community and the deterioration of mental and physical health, to name a few. While certain kinds of focused economic growth are necessary to address wicked problems (such as the alternative energy sector) economists, politicians, business and the media generally assume that growth of all kinds is a panacea for most problems. Challenges to this assumption are usually dismissed as uniformed or naive. And yet there is a compelling body of thought that critiques the dominant economic paradigm and proposes compelling alternatives. Environmentalist Michael Lockhart identifies four damaging forms of economic growth: “jobless growth, where the economy grows, but employment doesn’t; ruthless growth, where economic growth benefits the rich; rootless growth, where economic growth starves people’s cultural roots; and futureless growth, where the present generation squanders resources needed by future generations” .

In recent decades there have been many initiatives to develop alternatives. Some of these have been aimed at encouraging corporations to behave more responsibly within the constraints of the existing paradigm. The circular economy, industrial ecology and the triple bottom line framework, and more environmentally friendly forms of production such as large-scale organic farming, are examples of approaches that have been taken to mitigate the social and ecological impact of the global economy within the context of globalisation. Similarly, the proposed Green New Deal (as it is currently framed) while ecologically and socially beneficial, leaves unchallenged many underlying economic assumptions.

Other efforts are aimed at constituting new economic paradigms that are alternatives to the globalized, growth driven economic system as a whole. These focus on the development of new kinds of decentralized, equitable, integrated and convivial economic systems which would be woven into the social and ecological fabric of the cities and regions to which they belong. Most material and non-material needs would be satisfied locally, while others would through regional and global networks.

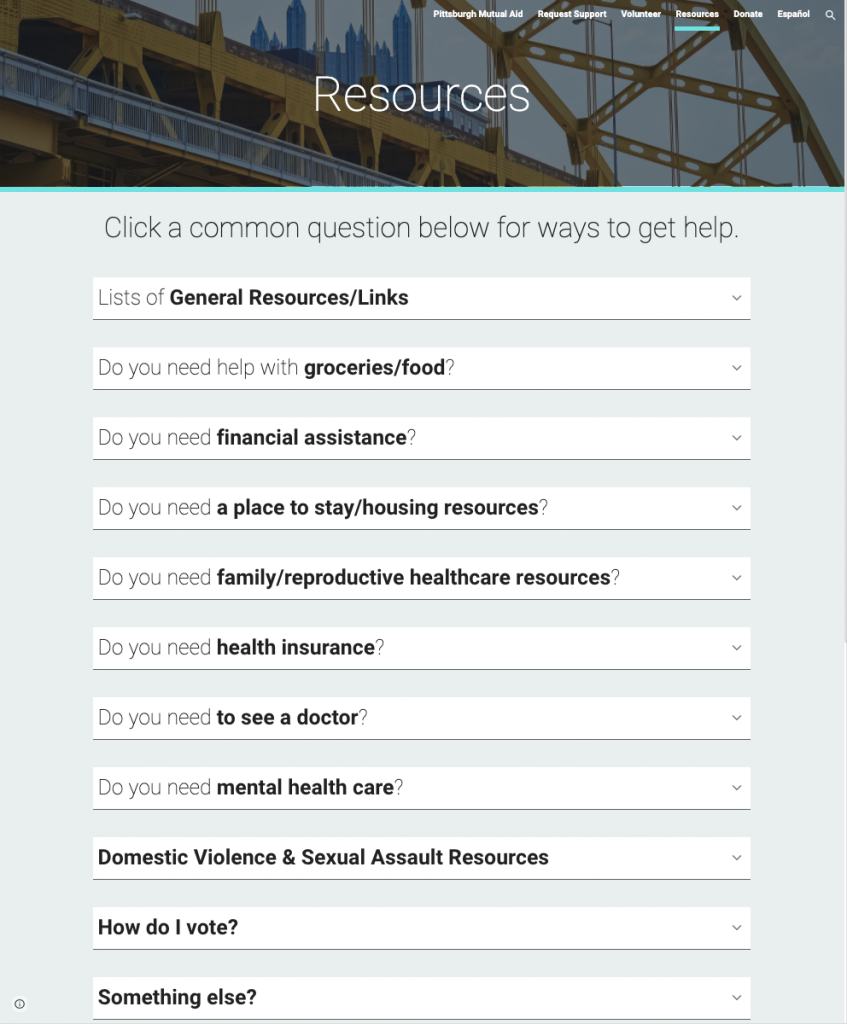

Many communities have already begun to experiment with new forms of currency and banking systems, are founding socially and environmentally responsible businesses (which are often cooperatively owned) and are developing new forms of housing, and localised agriculture, energy and manufacturing systems. More systemic approaches at local and regional levels include municipal/collective ownership and management of aspects of the economy (such as utilities, energy and communication networks); the transferal of assets from private ownership to the commons (such as land and urban spaces); and import substitution, the substitution of locally produced goods and services for those that were previously created/imported from other places (which would create and rejuvenate local and regional economies).Approaches such as the circular economy and the Green New Deal have potential to be employed at multiple systems level, from the global to the local., also have great potential at local and regional levels.

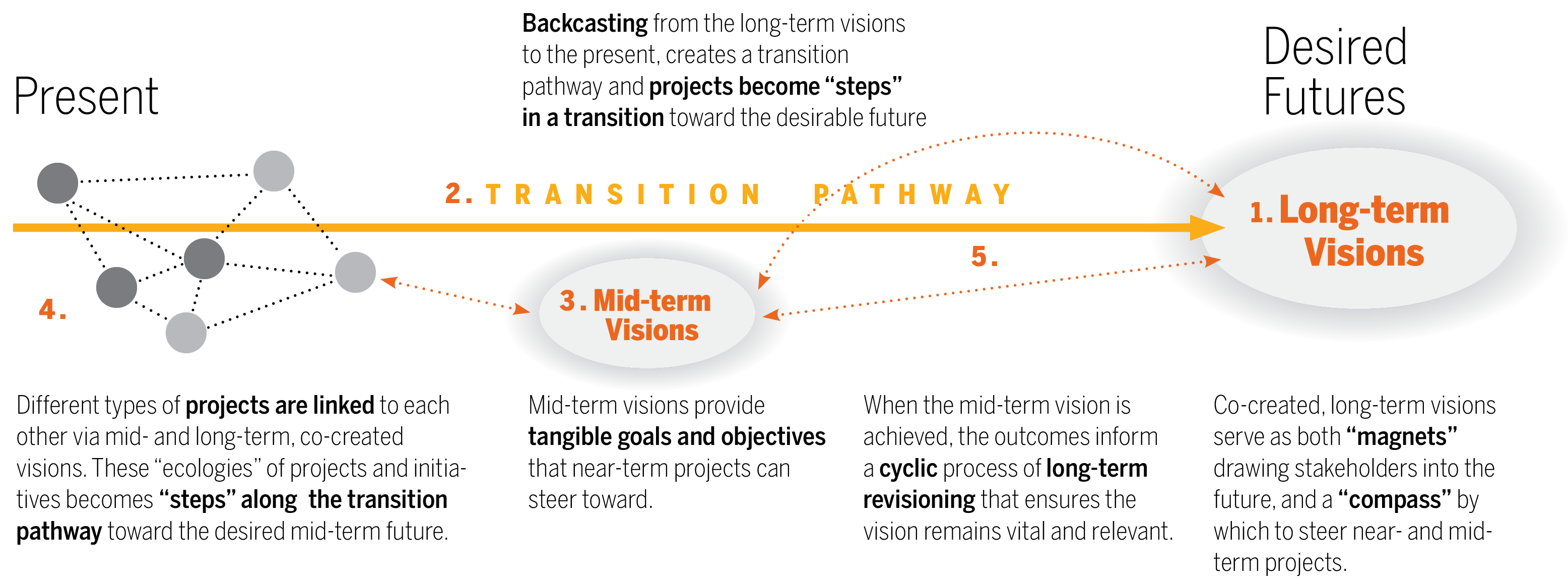

In this class we will discuss in detail some of these approaches to alternative economies, the ways in which the dominant for-profit paradigm impedes the ability of societies to transition to more sustainable, place-based lifestyles, and how transition designers integrate these initiatives and proposals into both long term future visions and present systems interventions. into both long term future visions and present day systems interventions.