This class will focus on the way in which both wicked problems and conflictual stakeholder relations are caused, underpinned or exacerbated by systems of oppression, racism and privilege. Because Transition Design is concerned with seeding and catalyzing systems-level change, this class will focus on issues related to diversity, equity and uneven power relations from a systemic point of view rather than focusing on individual experiences and perspectives.

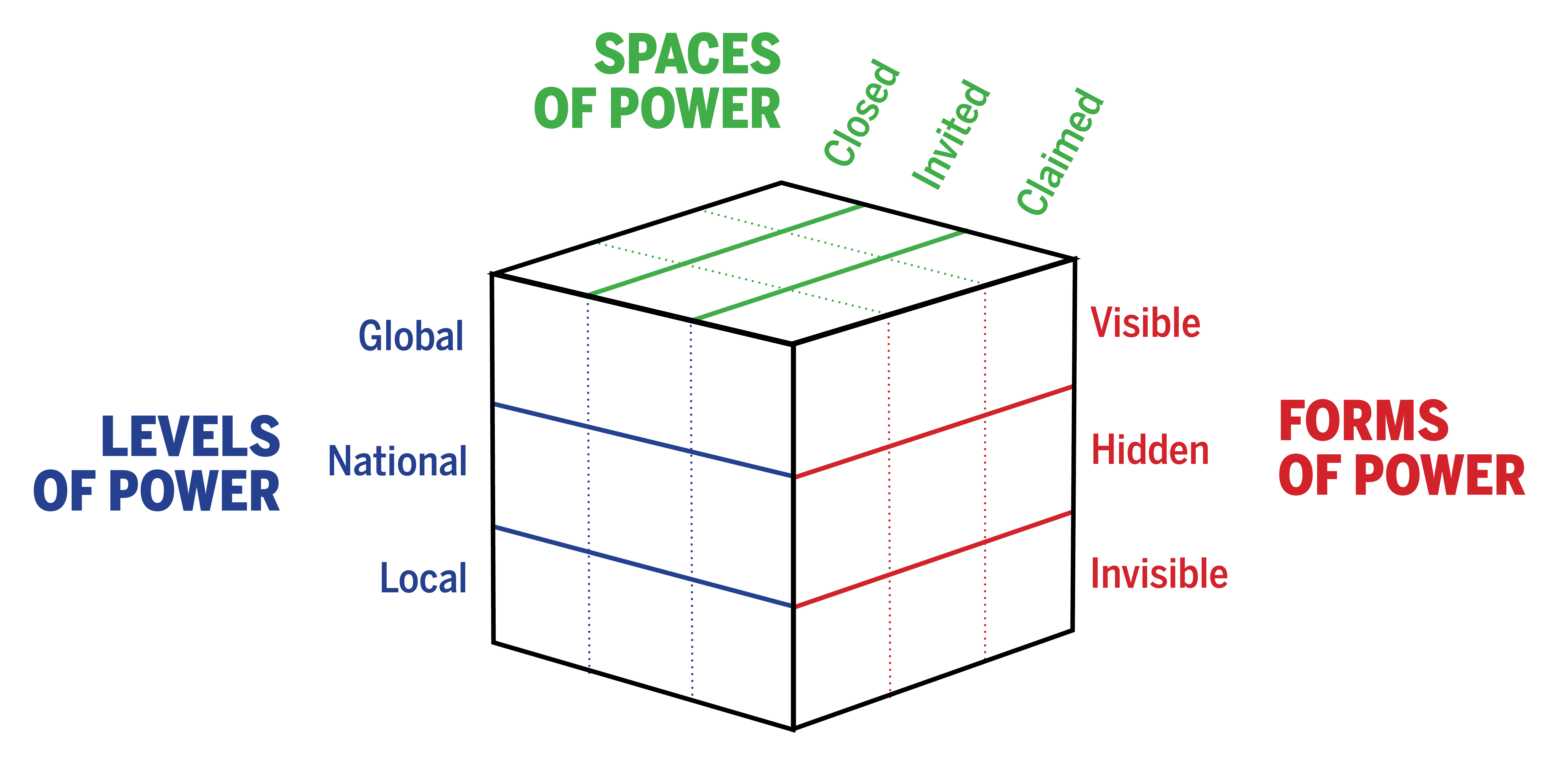

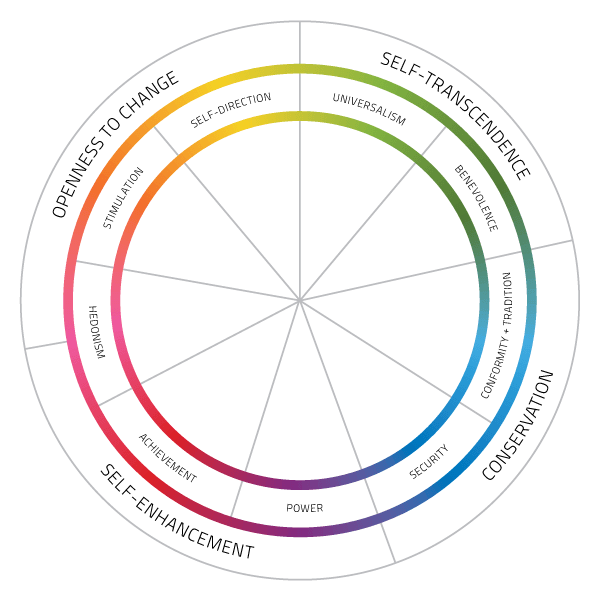

Systems of oppression (based upon race, gender, class, language, sexual orientation, religion, culture, etc.) are both institutional (policies and practices at the organizational or sectoral level that perpetuate oppression) and structural (refers to how these effects interact and accumulate across institutions and across history). A society’s institutions, structures, laws, beliefs/norms, and practices that are embedded in its fabric are all implicated. All of these conspire to oppress and discriminate against certain groups, while empowering and conferring privilege upon others.

The Friends of the Earth report Why Gender Justice & Dismantling Patriarchy, offers an excellent description of the way in which multiple systems of oppression are interconnected and interrelated. For example, they argue that patriarchy (as a form of systemic oppression) is interlinked with other dominant economic, social and cultural systems that mutually reinforce each other to replicate, maintain and reproduce each other’s hierarchy and power (known the “status quo” or intersectionality): “These [related] systems of oppression are capitalism, class oppression, racism, neocolonialism and heteronormativity. People also experience different forms of systemic discrimination in their daily lives, due to their special physical and mental needs, age, education level, religion, etc.”

In A Structural Analysis of Oppression, authors Sandra Hinson and Alexa Bradley argue “a person lives within structures of domination and oppression if other groups have the power to determine her actions. Individuals experience oppressive conditions because they are part of a group that is defined on the basis of shared characteristics such as race, class, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, nationality, age, ability, etc. These major social groups have specific attributes, stereotypes and norms associated with them. Individual memberships in these groups are not necessarily voluntary. It is not necessarily acknowledged either.” They go on to propose five forms of oppression: 1) Exploitation; 2) Marginalization; 3) Powerlessness; 4) Cultural Dominance; 5) Violence.

In her book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, author Isabel Wilkerson analyzes three historical caste systems: the caste system of Nazi Germany, the millennia-long caste system in India and the race-based caste pyramid in the United States and says “Each version relied on stigmatizing those deemed inferior to justify the dehumanization necessary to keep the lowest-ranked people at the bottom and to rationalize the protocols of enforcement. A caste system endures because it is often justified as divine will, originated from sacred text or the presumed laws of nature, reinforced throughout the culture and passed down through generations…the hierarchy of caste is not about feelings or morality. It is about power—which groups have it and which groups do not. It is about resources—which caste is seen as worthy of them and which are not, who gets to acquire and control them, and who does not. It is about respect, authority, and assumptions of competence—who is accorded these and who is not.” (pp 17-18).

Transition Design argues that mapping both problem and stakeholder relations has the potential to reveal these hidden systems of oppression and 1) enable us to address the wicked problems that arise out of them; 2) and reveal approaches to dismantle them. The National Equity Project (NEP) is a leadership and systems-change organization committed to increasing the capacity of people to achieve thriving, self-determining, educated and just communities. They argue that systemic oppression manifests on four systems levels: The Individual, The Interpersonal, The Institutional and The Structural, and and gives examples at each level:

Individual Level: A teacher holds an unconscious mental model that her students of color are not “college material.” This belief, left unchecked, leads to lower expectations of work quality, which allows for less rigorous teaching methods, and finally produces a gap in the actual skills and preparation of these very students. Similarly, a college counselor might push lower-income students toward community colleges or job training programs while counseling more privileged students to apply to four-year universities. These scenarios are all too real and, we would argue, a result of unexamined belief systems nurtured by an oppressive system.

The Interpersonal: By interpersonal, we mean the interactions between individuals that play out, both within and across difference. These are where the individual and the systemic levels of oppression intersect. These interactions are playing out constantly, within institutions and in the private spheres of life. Much of the interpersonal level manifests through discourse—how issues and situations are framed, talked about, not talked about.

The Institutional: By institution, we mean a single school or organization with its own internal set of norms, policies, and practices. On this level, we might witness a discipline policy that correlates to a disproportionate number of African American boys being sent out of class or a master schedule that de facto tracks English Language Learners into lower-level coursework. It may be that an organization creates a culture centered on dominant culture that makes it inhospitable to people of color. Though one might argue that these policies stem from individual belief systems, the institutional lens reveals how an organization’s patterns are self-sustaining and thus more than the sum of its individual actors.

The Structural: Structural oppression involves the macro-relationship between institutions that perpetuates or even exacerbates unequal outcomes for children. Despite its title, we would posit the “No Child Left Behind” Act as a prime example of structural oppression. In her recent piece “A Nation’s Education Left Behind”, former Assistant Secretary of Education Diane Ravitch wrote in 2011: We have now had ten years of No Child Left Behind, and we now know that there has been very little change in the gaps between the children of the rich and the children of the poor, between black children and white children. Just this week, the federal government released the urban district test results and we could see that the gap remained as large as ever. After ten years of NCLB, the children at the bottom were still at the bottom. By critically analyzing this policy, we can see how politicians colluded with financial interests to create a hollow discourse of opportunity while in fact sowing the seeds of oppression.