Transition Design argues that wicked problems must be framed within radically large spatio-temporal contexts that include the present (how the problem manifests and who it affects), the past (how the problem emerged and evolved over dozens of years or decades), and the future (what we want to transition toward). This class discusses how to map the historical evolution of a wicked problem in order to reveal insights from the past that can inform both long-term future visions and present-day systems interventions.

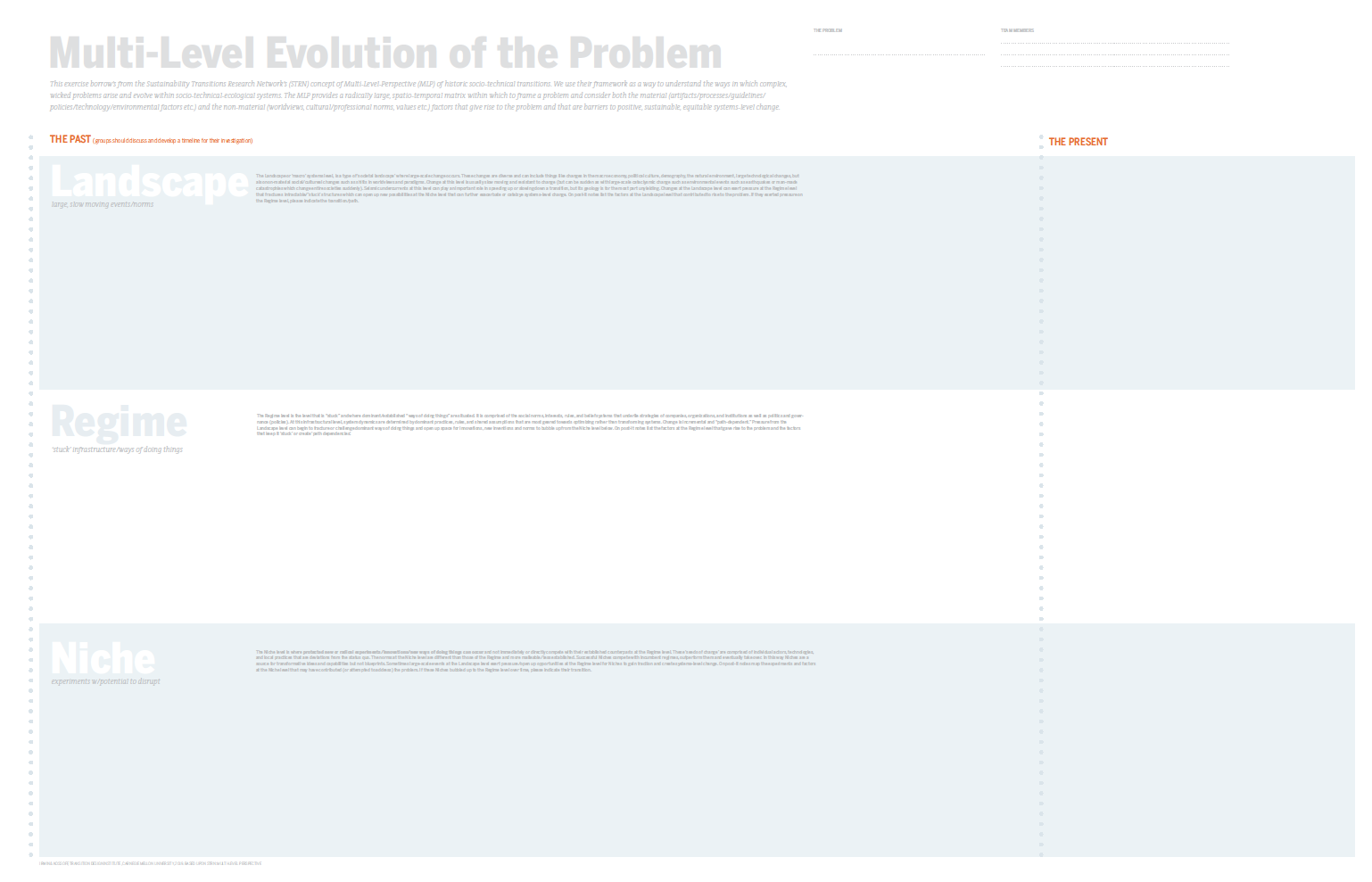

Transition Design draws/builds upon Transition Management theory and the work of the Sustainability Transitions Research Network (STRN) which focus on how socio-technical systems change and transition over long periods of time. This body of research can help us ascertain when and how issues related to a wicked problem arose and, over long periods of time, began to constellate and evolve to form a wicked problem. It uses the Multi-level Perspective framework (MLP) to map the systems transition at three key levels:

The Landscape Level: at this macro systems level the societal landscape is determined by changes in the macro economy, political culture, demography, natural environment, and worldviews and paradigms, which are usually slow moving and resistant to change. These seismic undercurrents can play an important role in speeding up or slowing down a transition, but their geology is for the most part unyielding.

The Regime: this meso systems level comprises the social norms, interests, rules, belief systems, technologies, infrastructures and built environments through which the status quo operates and reproduces itself. The regime is managed through networks of companies, organizations, and institutions as well as through politics and governance (policies and laws) at multiple levels of scale (local, national, international). Within the regime, system dynamics are determined by dominant practices, rules, and shared assumptions that are most geared towards optimizing rather than transforming systems.

The Niche: this micro systems level consists of individual actors, technologies, and local practices. Variations to and deviations from the status quo can occur as a result of new ideas and new initiatives, such as new techniques, alternative technologies, and innovative social practices. “Incubation” is a term often used to describe how innovative, risk-taking experiments are protected from regime norms and have the opportunity to take root and sometimes destabilize the Regime.

Interactions among the three levels (landscape, regime and niche) are social, technical, institutional, infrastructural and normative and involve both material and non-material factors. The networks of relationship within the regime and landscape become progressively more entrenched, inertial and resistant to change as their scale and complexity increases. Eventually large systems become “locked in” to particular trajectories or transition pathways. In other words, although socio-technical systems (and wicked problems) are constantly ‘in transition’, they get set in their ways, just like people do.