Transition Design resembles Chinese acupuncture in its approach. Acupuncturists look for points of intervention that have the greatest potential to transition the system back into balance and health. Where the needles are placed can seem wildly counter-intuitive, but is actually based upon a deep understanding of the body’s systems dynamics. Transition Design proposes a similar approach to seed and catalyze the transition of our socio-technical-ecological systems toward sustainability. A group of scientists, engineers and researchers in northern Europe (STRN) have been mapping the anatomy of historical socio-technical transitions for nearly two decades—essentially providing a roadmap for initiating transitions. We believe this can be supplemented by approaches that seek to understand how social practices, human behavior and worldview can also be strategies for change and designed interventions.

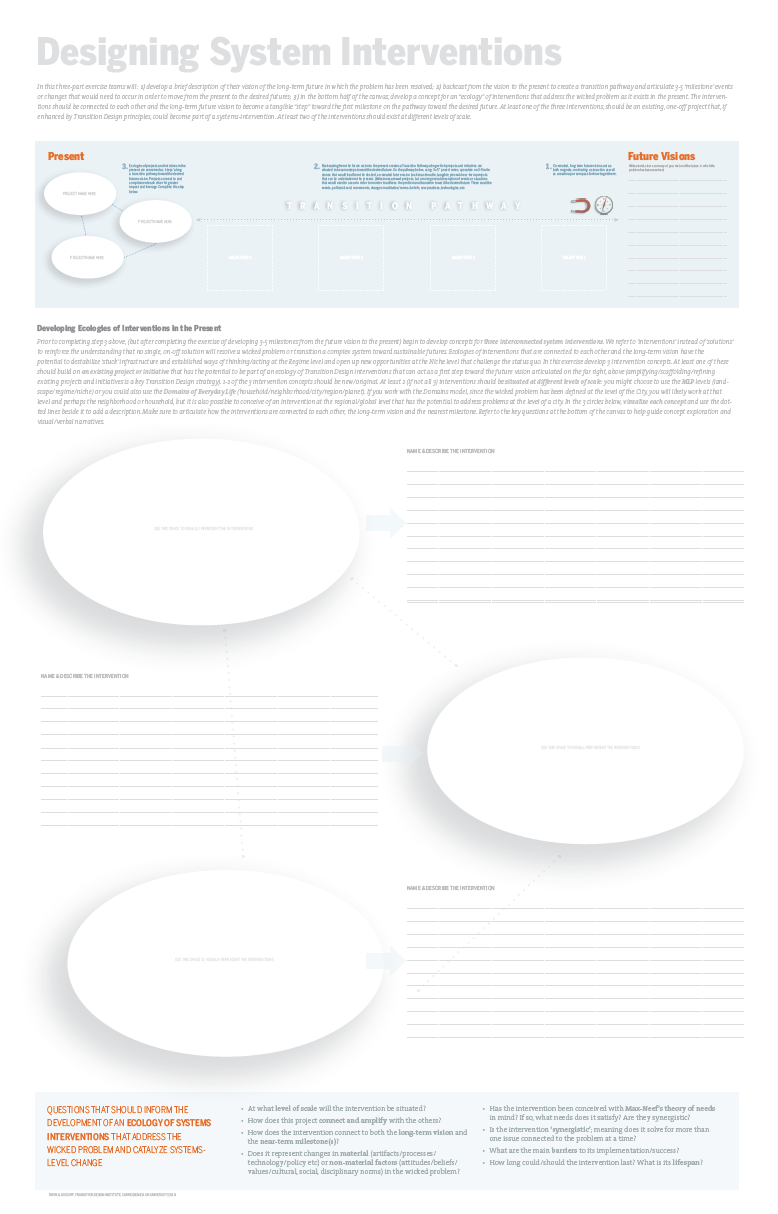

One of the primary ways that Transition Design differs from other design approaches is its emphasis on ‘design for systems-level change’ which can take many years or even decades. Instead of thinking in terms of one-off solutions, that are completed within relatively short time frames, Transition Design thinks in terms of designing ‘systems interventions’ that are implemented at multiple levels of scale, over short, mid and long time horizons. These interventions are connected to each other as well as the long-term vision and near-term milestones that are positioned along a “transition pathway” formed by backcasting from the future vision to the present.

‘Ecologies of interventions’ have the potential to ‘transition’ a system (a wicked problem, an organization or entire societies) over time, toward new, sustainable/preferable futures. Because we can never predict how a complex system will respond to these interventions (because of their self-determining dynamics), periods of design/action must be balanced with periods of waiting/observing to see how the system responds. This will challenge our dominant paradigms that call for quick, decisive action that yields quick, profitable results. For this reason, Transition Designers will need to create compelling communications and narratives that explain why both action and observation are crucial to designing over long periods of time.

In this class we will discuss the emerging Transition Design approach and in particular, how teams’ research and the learning from the previous assignments can inform the conceptual development of 3 or more ‘designed interventions’ aimed at resolving the wicked problem.